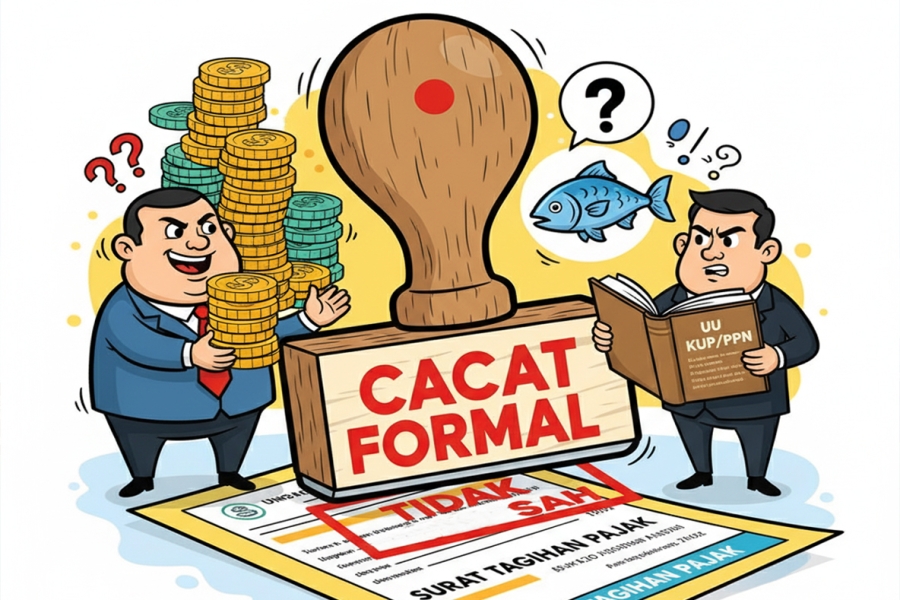

The application of administrative sanctions in Indonesia’s tax system is largely determined by formal legal principles, particularly those related to a taxpayer’s registration status. This critical issue emerged in a dispute filed by PT BHN against the tax authority’s decision rejecting the cancellation of a Tax Collection Letter (STP) for the VAT Period of June 2019. The core question in this case was: can administrative sanctions under Article 7(1) of the General Taxation Provisions Law (UU KUP) for late VAT return filing and Article 14(4) of the same law for failure to issue tax invoices be imposed on a taxpayer who, although materially required to be registered as a PKP, had not yet been formally registered at the time of the disputed period? This case highlights the complex interplay between material obligations and formal registration requirements under the Value Added Tax Law (UU PPN) and their legal implications for administrative sanctions.

The dispute divided the views of the two parties. The Directorate General of Taxes (DGT) found that PT BHN’s turnover in February 2019 had exceeded IDR 4.8 billion, the threshold for small enterprises as stipulated in Article 3A(1) of the VAT Law. Based on this finding, the DGT argued that PT BHN had materially fulfilled the criteria of a Taxable Entrepreneur (PKP), even though it was only formally registered as a PKP on March 27, 2024. Therefore, the DGT maintained that the taxpayer’s VAT obligations had arisen as soon as the turnover threshold was exceeded, and the issuance of the STP imposing administrative sanctions was considered valid, despite the later formal registration.

However, PT BHN contested this view with strong formal-procedural arguments. The company argued that administrative sanctions under Article 7(1) and Article 14(4) of the Tax Administration Law can only be imposed on taxpayers who have been formally registered as PKP. Since PT BHN had not yet been registered as a PKP during the June 2019 tax period, the formal VAT obligations forming the basis of the sanction had not yet arisen in law. Furthermore, PT BHN is engaged in the trade of fresh fish (such as tuna, skipjack, and mackerel) purchased directly from fishermen without any further processing other than cooling, which qualifies as basic food commodities exempt from VAT. Therefore, the issuance of the STP was deemed procedurally flawed.

In its judgment, the Tax Court Panel held that administrative actions such as PKP registration constitute a formal prerequisite that gives rise to obligations to file VAT returns and issue tax invoices. Without a formal registration as PKP, the STP imposing administrative sanctions lacked legal validity and must therefore be annulled. Moreover, because the sale of fresh fish falls under non-VATable basic commodities, the imposition of VAT-related administrative sanctions had no legal basis, even though the DGT argued that the taxpayer’s turnover had exceeded the PKP threshold. Accordingly, the Tax Court declared that the STP issued by the DGT was formally and materially defective and must be revoked, as it contravened the principle of formal legality and legal certainty for taxpayers.

This decision carries significant implications for tax practice, particularly for taxpayers whose sales approach the PKP threshold or who operate in sectors dealing with non-VATable goods such as fresh fish. The key lesson is that while the DGT has the authority to assess sanctions based on material obligations, the formal registration as a PKP remains the determining factor for the legality of any VAT administrative sanction before the Tax Court. For taxpayers, the best strategy is to be proactive in applying for PKP registration immediately after surpassing the turnover threshold, while also ensuring that the classification of goods or services being traded complies with VAT regulations to avoid potential disputes in the future.

A Comprehensive Analysis and the Tax Court Decision on This Dispute Are Available Here